I once led an AI competency center for a global information technology services company. Our mission was to explore the potential of AI, build innovative demonstrations, raise awareness on how to apply to business advancement around the world, and establish standards and templates our consultants could use to accelerate adoption. That’s a mouthful, I know, but it should sound fun, because it was a blast, perhaps the best job I ever had.

We started this effort near the front end of when machine learning took the industry by storm and Geoffrey Hinton became our hero. One of my team members knew him personally, studied under him as a college student, and kept promising to arrange a meeting with this charming man we now call the Godfather of AI. Geoffrey’s schedule never accommodated, unfortunately. The brilliant champion of the neural networks, with an injured back that kept him from ever sitting down while he worked, somehow never quite had a free hour for us. We understood, forgave him. This future Nobel Prize winner remained an inspiration as we developed our AI demonstrations.

I became aware, in these early days, of both the dangers of AI hype and the folly of AI dismissal. With machine learning, we possessed new predictive powers, when the data supported our desires, but we also yielded a weapon that might easily trick us into doing harm to ourselves or others. That potential for damage jaded many, who then made the mistake of dismissing AI as only overhyped and immature. One of the large voices on the naysayer side was Gary Marcus. He’s been sniping at Geoffrey Hinton for decades, and Geoffrey has made a career of proving Gary wrong. Yet now that we’re immersed in the disruptive power of AI, bringing upheaval to our lives from nearly every direction, we might imagine the naysayer’s revenge. Gary may get to claim he’s been correct all along, and we might even secure a better world from his triumph.

Hinton concentrated on modeling digital systems after the neural pathways of our biological human intelligence and arrived at exciting forms of narrow AI, capable of doing many discrete tasks better than humans. Applications arose so quickly and became so pervasive, we hardly remember to give credit to AI when it predicts how long our drive across town will take, or completes the sentence we’re writing, or transcribes the conference call we’re attending, or selects the next song on our music stream that we’re likely to enjoy, or any myriad of other improvements we’ve come to take for granted. And forget about defeating an AI at Chess over even Go. These great thinking games, long considered the realm of the most intelligent humans among us, are now owned by AI. What remains elusive, though, is the power to reason broadly beyond the confines of a carefully controlled training set. The computer you can’t defeat at Go may know almost nothing about the world beyond, doesn’t appear to know who or what you are, or even that its playing a game. This is where Gary Marcus asserts neural networks will never have the power to reason generally about the world, a dead end path on the journey toward human like intelligence.

Now I wonder if Marcus had some doubt about this dead end when he first interacted with large language models (LLMs). I know I did. But it was fleeting. ChatGPT was stunning, remains stunning, actually, but interact with it for long and you eventually see the limitations.

My old boss, from my AI consulting days, wanted me to create a Generative AI practice soon after ChatGPT arrived. It seemed natural to rerun the play we’d just run on machine learning and predictive AI, create a new competency, a new revenue generating consulting resource monetizing the Generative AI game. I surprised everyone, including myself, by turning down his proposal. My hesitancy was due to seeing more hype than potential. I didn’t know whether I was right or whether I had just reached the end of my road, becoming an old fossil in the IT industry unable to visualize the future, but regardless, I just didn’t see it.

The way I explained it to my boss went something like this: Imagine a new guy moves into the office next door to you. As you get to know him, you discover he’s whip smart, possessing encyclopedic knowledge about every aspect of the world, it seems. Ask him anything and almost before you finish the question he begins eloquently spooling out a comprehensive answer. Then you discover he’s capable of astonishing creativity. Ask him to author an original poem about the feud between Kendrick and Drake using Shakespearean style and without a moment’s thought, he somehow pulls it off, even sticking the landing with the final verse. But then, as these exciting days of discovery with your new officemate progress, you begin to notice he’s often full of shit. There’s no lack of confidence when he’s wrong. He always seems completely sure of himself. But there are these moments when he pontificates on how a pound of feathers weighs less than a pound of gold and you’re thinking come on, man, we learned that was wrong in grade school. Or there are the moments when he’s sighting details from a paper that doesn’t exist, completely making it up, but still sounds so full of certainty. Now how long does this go on before you find yourself avoiding the guy? If a significant percentage of what he tells you is bullshit, you realize you have no choice but to doublecheck all of it. Then instead you begin keeping your office door closed so that he doesn’t interrupt. You time your arrivals and departures so that you avoid running into him in the hallway. Because there’s you’re busy. You’ve got real work to do.

That conversation occurred years ago now, but it might play out the same way today. I continue to be amazed by what LLMs can do. And I confess, I don’t actually avoid bumping into LLMs in the hallway. Instead, I use them. For example, my cybersecurity classes include labs where students use Microsoft Copilot to author code capable of searching for vulnerabilities on servers. And I love when someone invites Grok to a Twitter thread, despite the way I feel about Musk. The input from Grok is always stimulating. Still, I regard Grok’s take as only opinion until I’m afforded the time or interest to verify. Those who don’t operate this way frighten me.

The other day I received a text claiming to be from my state warning I had only twenty-four hours to pay a traffic toll to avoid penalty. It wanted me to click a link that didn’t end in colorado.gov or any domain we might expect. These messages are getting better at sounding legitimate, but are still a bit obviously junk. For amusement, I asked Gemini about the domain, wondering if we might create an LLM based screener trained on the latest scams to read these messages and filter away. As I sought to learn if Gemini’s training set included necessary awareness, Gemini surprised by explaining the domain is used by the state of Colorado for transportation department business. It essentially gave the scammer’s view on the situation, perhaps finding somewhere in its knowledge base this false assertion and predicting that’s what I needed. I next asked Gemini about the domain again, but added the word “scam” to the end of the original query. This time it warned this domain was used in malicious links I should not dare click. Again, we should all be frightened by this. LLMs have no hesitancy, no adequate due diligence, as they confidently steer us either towards danger or away from it. Their job is predicting what we might want to hear in a way that can easily go wrong. Musk wants to replace most of our government employees with such “minds” and we should all be screaming about the potential ruin.

LLMs have accelerated us toward a moment where we have two competing camps on AI thought leadership. One is worried Artificial General Intelligence is imminent and we’re not prepared for the existential danger. They fret about the alignment challenge, some way to ensure AI’s goals always remain compatible with our own. Hinton is near the center of this crowd, and he describes the threat best when he suggests understanding life in a world where we’re no longer the most intelligent just requires inhabiting the point of view of a chicken. Mull over that while you next snack on Popeye’s. The other camp believes this is silly. They see nothing approximating general intelligence in today’s capabilities and view the alignment worries as hype, perhaps maliciously aimed at grifting us for hysterical amounts of investment in dead end technology. They go on about TESCREAL, Timnit Gebru’s acronym for various overlapping dubious and nefarious movements from big tech, which all seek to use threat of human extinction to drive us toward their dystopian visions of the future. These sober skeptics dismiss LLMs as mindless, stochastic parrots, tricking anthropomorphic fools into giving undue power to tech broligarchs.

The crux of the argument between these movements is rationality. Hinton believes instantiating the digital neurons of a vast network with properly weighted data leads to predicting rational, well-reasoned conclusions, not unlike the way our human brains actually work. Marcus dwells on the hallucinations, the way these black box brains flail when they reach the edge of their training set and have no general awareness to ground them. Alternative approaches to rationality have been brittle and tediously plodding, failing to reach much beyond the logical scripting our programs have always depended on. If we had listened to Marcus all along, we might not have today’s navigation systems and advanced surveillance systems and better weather forecasts and translation software and lifelike videos of talking cats and bots that’ll debate capitalism with you on Twitter no matter the hour. But listening to Marcus now, when the Hinton types believe only a scaling challenge separates the human species from arriving at the fate of chickens, has new appeal.

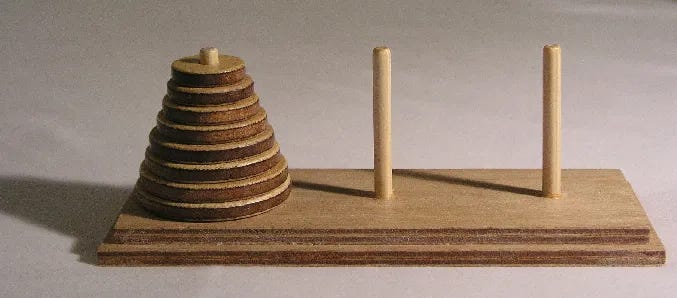

Hinton claims he became alarmed by the proximity of AGI when he heard an LLM explain why a joke was funny. They do this well and it’s truly remarkable. But Marcus would explain the LLM doesn’t know why a joke is funny, instead only predicts what words explain this phenomenon. Hinton might counter by asking if there’s any real distinction there. Point, counterpoint, point, and so on. The back and forth of these arguments have been reenergized by a recent study from Apple titled, “The Illusion of Thinking,” which demonstrates how LLMs fail to scale up reasoning in the same way as humans. These strange beasts that pass the bar exam but stumble performing division on four digit numbers, also embarrass themselves on math puzzle games, such as Tower of Hanoi. This has been an occasion for Marcus to say, “told ya.”

If unknown innovations must arrive on an unpredictable timeline before the doom of AGI dawns, we can sigh with relief, perhaps invest our worries instead in the other ways AI is going to slaughter us, such as by assassinating democracy and reinvigorating fascism.

Because AGI is not the chapter where we’ll first encounter an alignment problem. Humans have already unleashed alien forms of intelligence misaligned with humanity’s goals. We created the corporation, for example, which has a self perpetuating mind of its own, became a profit driven monstrosity spreading like a cancer across the surface of the earth, spewing planet choking carbon dioxide and crushing millions with poverty. The Citizens United ruling sparked super spread conditions, where money became speech, and then corporations became the only voices heard. None of this is aligned with the human values essential for our species to survive. If digital AI deals us the final death blow, we shouldn’t forget to give corporations credit for a good head start.

I mostly left the study of AI when LLMs arrived. While the entire IT industry scrambled toward complete reset on the promise of these clever new bullshitters, I simultaneously saw cyber crime exploding. And this was no escape, of course. The cyber crime arms race is propelled by AI. LLMs turn out to be the best scammers we’ve ever known.

Now all of my interests converge on the fate of the world I leave my grandchildren. I don’t know whether Skynet soon seizes the robot plants, begins mass producing murder bots, and exterminates the human beasts who’ve done so much harm to the planet, or whether the Peter Thiels manage to psyop most of humanity, steal all representative data, and manipulate us into becoming Curtis Yarvin’s dreamed of biofuel our white overlords feel they deserve. Either way, both of the sciences I’ve devoted my working life towards will possess the bloody hands.

Hinton vs. Marcus? Well, let’s hope their debate even matters. Assuming it does, cheer for Marcus.